Maybe This Was a Mistake

“Maybe this was a mistake."

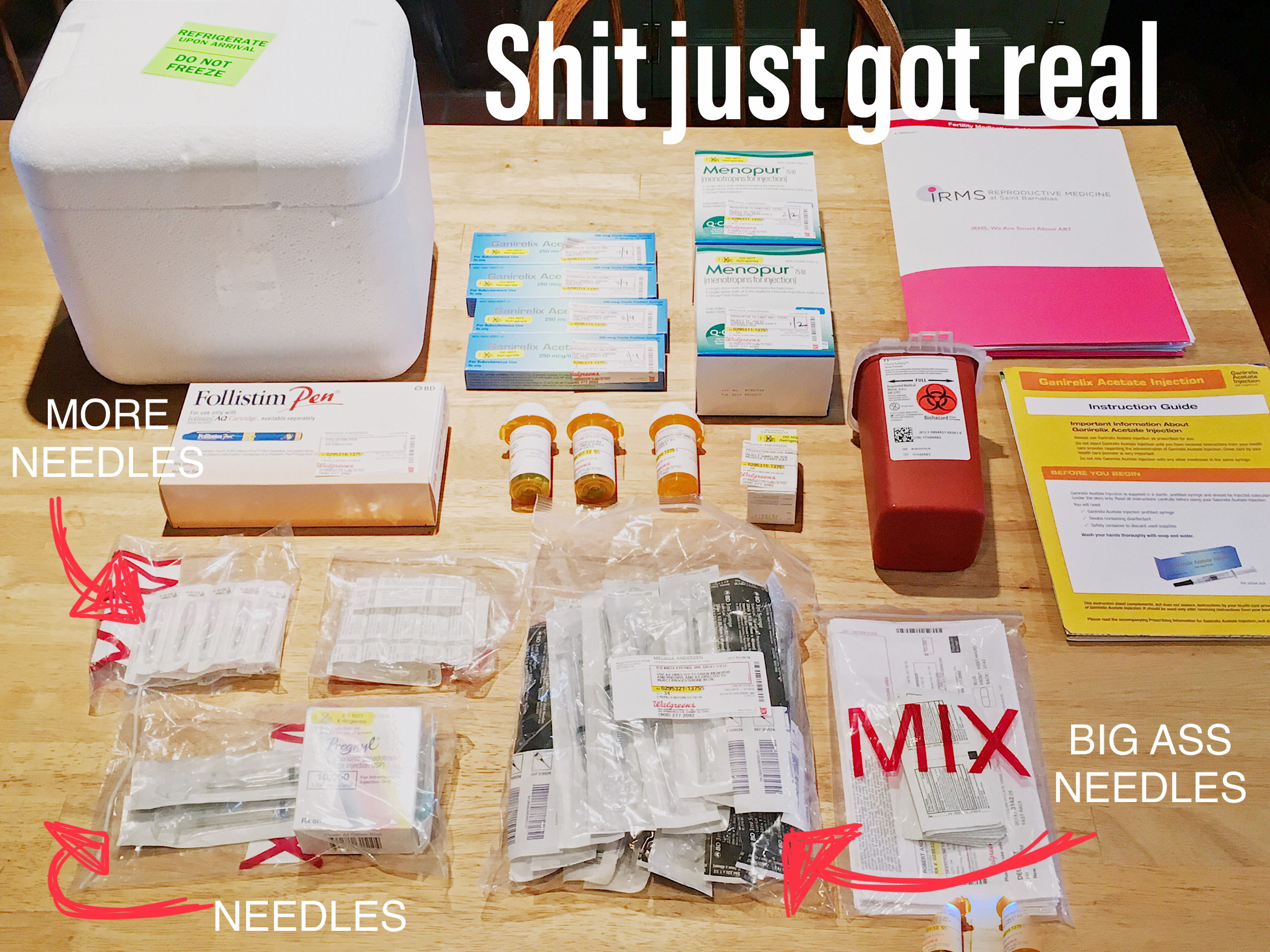

No, I didn’t say that to Melissa about IVF. I was talking about the blog. After a few posts, especially the most honest and vulnerable ones, people began reaching out to me with genuine concern.

“Are you depressed?” “Are you ok?” “Do you need anything?”

I felt bad. I don’t want people to worry about me. I kept scolding myself with a line from the pilot episode of The Sopranos: “Nowadays, everybody’s gotta go to shrinks, and counselors, and go on Sally Jessy Raphael and talk about their problems. What happened to Gary Cooper? The strong, silent type. That was an American. He wasn’t in touch with his feelings. He just did what he had to do. See, what they didn’t know was once they got Gary Cooper in touch with his feelings that they wouldn’t be able to shut him up! And then it’s dysfunction this, and dysfunction that, and dysfunction vaffancul!”

First I was struggling with infertility. Now I’m bucking masculine convention by talking about my feelings. Oh god, I’m a corny millennial convention. But the great irony of the Tony Soprano quote is the fact that Tony admires Gary Cooper for something that Tony can’t be. Tony spends the next 86 episodes of the show trying to get in touch with and better understand his feelings, and his failures as a character, and as a human, are often based on his failure to do exactly that.

Melissa and I didn’t start this blog to become victims. It was never about sympathy. We wanted to document a moment in time. We didn’t want this experience to define us, but suddenly it felt like it was. I opened up in my writing and I worried that people were now thinking of me as devastated and damaged, characterized by a single struggle. Without a doubt, when you’re dealing with infertility, it can feel all-consuming, but it is still just one element in a multifaceted life. Through our writing, we were looking to, quite literally, define this experience. I don’t mean that in an empowering “grab the bull by the horns,” “you got this” way. I mean that we wanted to define it intellectually. It was a challenge to ourselves. We wanted to see how deep we could go as creators and writers to put into words what we were going through; to go to those places that we avoid articulating. We were seeking words for the pain, anger, and frustration that people in our shoes feel but do not talk about.

The bottom line is, this is like a lot in life - a struggle. Struggle isn’t just hard to go through, it’s hard to talk about. Joy is easy to define. Joy is what everyone shares. It floods our social media feeds. But pain is the most human of emotions. Pain is what makes us human. Later in that Sopranos scene, Tony finds his own nugget of truth: “Could I be happier? Yeah, who couldn’t.” Is there a better expression of what it is to be human? We could always be happier. Everyone has that anxiety and stress that keeps them from being present and keeps them up at night. For us, if it wasn’t infertility, it would be something else. Melissa and I aren’t more or less happy than everyone else, we’re just seeking to put our experience out there.

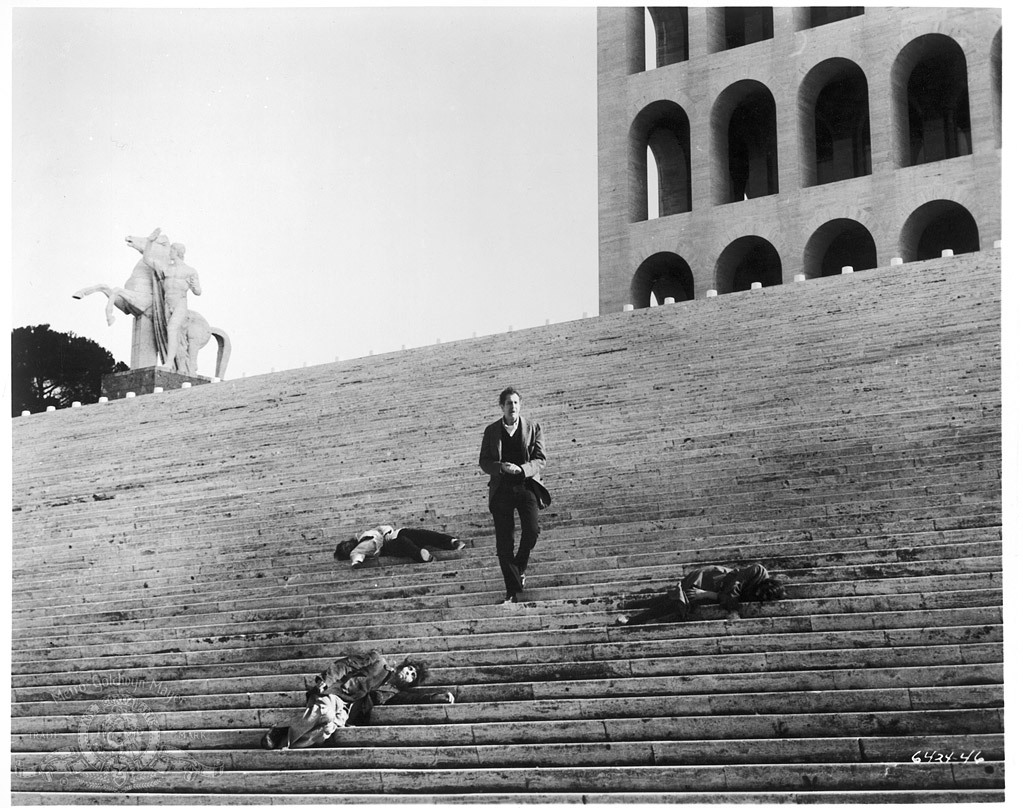

The bottom line is, like Gary Cooper, however we all feel, we all have shit to do. And the world, as a whole, is indifferent to our struggles. Bills need to be paid, work needs to be done, the dog ain’t going to walk itself. Life doesn’t stop for our feelings, so despite our struggles, we get out of bed in the morning and get to work. Speaking to emotion, understanding our oh-so-unmasculine feelings will not change our ability to do what we have to do, so why are we all so hesitant to be open? No matter what happens, Melissa and I are going to keep going forward in life. It would be one of life's great devastations to not have children. But don’t we all end up with great devastations? As Melissa likes to tell me, “We all have our cross to bear.” What can you do but move forward? And in the moment, what can you do but grin and bear it?

This doesn’t mean we have to sit around complaining all the time, but what’s wrong with genuine deepness and honesty? We’re conditioned to avoid and hide our pain. Pain is awkward. We don't know what to say. But pain is as much a part of life as everything else. We don’t need to hide how we feel to be strong silent types. It’s surface-level bullshit. Tony storms out of Dr. Melfi’s office and of course, proceeds to have another panic attack that will drive him back to her. Hiding the struggle does nothing. Vocalizing my pain and frustration hasn't made it more real; instead, it's made me feel free.